Note by the author

The foregoing is an excerpt from After Collapse (2021), written while much of America was burning from a so-called racial reckoning. I honestly don’t know what I think about that excerpt today. With recent events, I sense myself getting pulled back into nihilism, which includes the “cold logic of tit for tat and the blazing fires of ideology.” I want to hold onto the hopes reflected in the passage. But sometimes, our adversaries boldly exclude themselves from our hopes. Even in our best efforts to be Switzerland about distant affairs, there are those closer to home who would line us up for a firing squad, given the chance. Yet I know that people who hurt … they come from hurt. So it is and will be. At a time when terrorists are understood as freedom fighters and zombie hordes on campuses are chanting “from the river to the sea,” what can be said about our common humanity? I wish I knew.

The more fractured we become, it seems incumbent upon us to appeal to our common humanity. But if someone is shooting at you, when do you shoot back?

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

(W. B. Yeats, from The Second Coming)

Ann Arbor, Michigan, is a university town full of people you wouldn't think of as having many racists. But all that changed one day in 1996 when the Ku Klux Klan came to town. Keshia Thomas was among the protesters who turned out to express her disapproval. Thomas, an eighteen-year-old black high schooler, had had her own experiences with racism. So she wanted to join the protest.

According to reports, local police had organized the scene to keep the peace, so they kept protestors and marchers separated. All parties had stayed in control despite tensions running high. A procession of men in white robes and coned hoods walked along the thoroughfare. Far enough away, protestors aired their resentment. Then, events took an unfortunate turn.

"There's a Klansman in the crowd," said a woman with a megaphone.

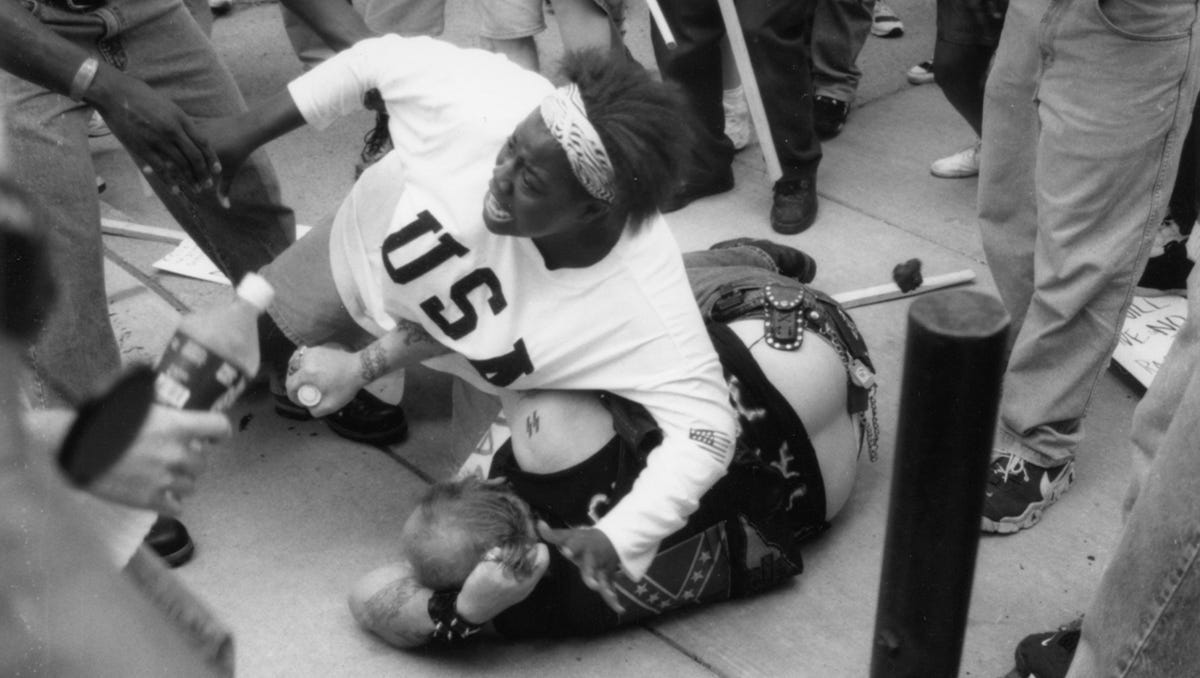

Thomas and her friends, black and white, had been standing next to a fence designed to separate the groups. They turned around to see a middle-aged white man wearing a shirt emblazoned with a Confederate flag. His arms bore tattoos with neo-Nazi symbols. The man tried to walk away from the group, but the protesters, including Thomas, pursued him.

A mob mentality took over.

"Kill the Nazi!" someone cried out. When the man tried to run away, the crowd gave chase. A group surrounded him. They began kicking him and beating him with their placard poles.

Keshia Thomas jumped into the fray, using her own body as a shield to protect a man who hated her by all outward appearances. She wept and cried out for the protestors to cease their violence as if to say this isn't who we are.

And cease they did.

A student photographer managed to capture images of the scene.

In revisiting this story and the photos, now decades old, they prompt us to ask a series of essential questions. Foremost is: what would possess Keshia Thomas to risk injury or worse to protect someone like this?

When she recounts it, she credits her religious faith. And who knows? When everyone around her was caught up in a flash of anger, maybe Thomas was guided by a divine hand. Still, had something else motivated Thomas?

We find clues in her own words:

For the most part, people who hurt... they come from hurt. It is a cycle. Let's say they had killed him or hurt him really bad. How does the son feel? Does he carry on the violence?

One rarely hears such wisdom in the words of teenagers. And yet, it had come forth from deep within her in an instant.

Fast forward a quarter-century.

Whatever forces led Keshia Thomas to act bravely, lovingly, and utterly without judgment, there is decidedly less of it today.

Our Common Humanity

Whenever there is conflict in the world, you'll hear someone make a plea to recognize our common humanity. That person is usually roundly ignored, either because the appeal gets lost in the heat of friction and faction or because it interferes with a collective desire for revenge. But in this refrain, however platitudinous, lies an important truth. Our common humanity forms the basis of our creation stories and secular humanisms. It is how we say We are not so different, you and I.

It is a call to civility.

Today, we are again witnessing the breakdown of civility and civil order. I say again because it's never really left us. It would be dishonest to claim there has ever been an era in which civility was a mainstay. War is uncivil, but our own Civil War was fought over that most horrific form of disrespect for one human being by another. Slavery was instituted well before America became a nation. Despite the stirring words of the Declaration, its very fact adulterated the Constitution.

What, then, does the Declaration mean in the twenty-first century?

"It’s 244 years of effort by Americans — sometimes halting, but often heroic — to live up to our greatest ideal," writes conservative columnist Bret Stephens. "That’s a struggle that has been waged by people of every race and creed. And it’s an ideal that continues to inspire millions of people at home and abroad."

Even after the bloody mess of 1860, almost a century passed before federal troops escorted the Little Rock Nine into their Arkansas high school. Before that day, there had been chain gangs, lynchings, and countless other indignities. Troubles remained well after a Memphis shooter made Dr. King a martyr for the cause of civil rights.

Still, little by little, things got better. Not perfect, but better.

If we think of our common humanity as the trunk of a Great Tree, we know that a few limbs must grow from the trunk, each finding its direction as it pushes outward or upward. Maybe these are broad ethnicities.

From the limbs, large branches grow and hold the world's major cultures. But the large branches divide into medium-sized branches, which are subcultures, and so on into small branches, which are even more distinct. These, in turn, divide into twigs of linguistic or regional variation on which you'll find the buds, leaves, and blossoms of wild diversity and local color. It can be easy to forget a Siberian Inuit has anything to do with a tuba player from New Orleans.

Yet everyone knows what happens to a branch if you saw it off.

“Power based on love is a thousand times more effective and permanent than the one derived from fear of punishment," wrote Mohandas K. Gandhi. But this is a lesson that must be retaught and relearned with each generation.”